あなたは「アシッドテスト」に合格できるか? - サイケデリックと精神的優生学について:後編

ジュールズ・エヴァンス

2020年8月30日

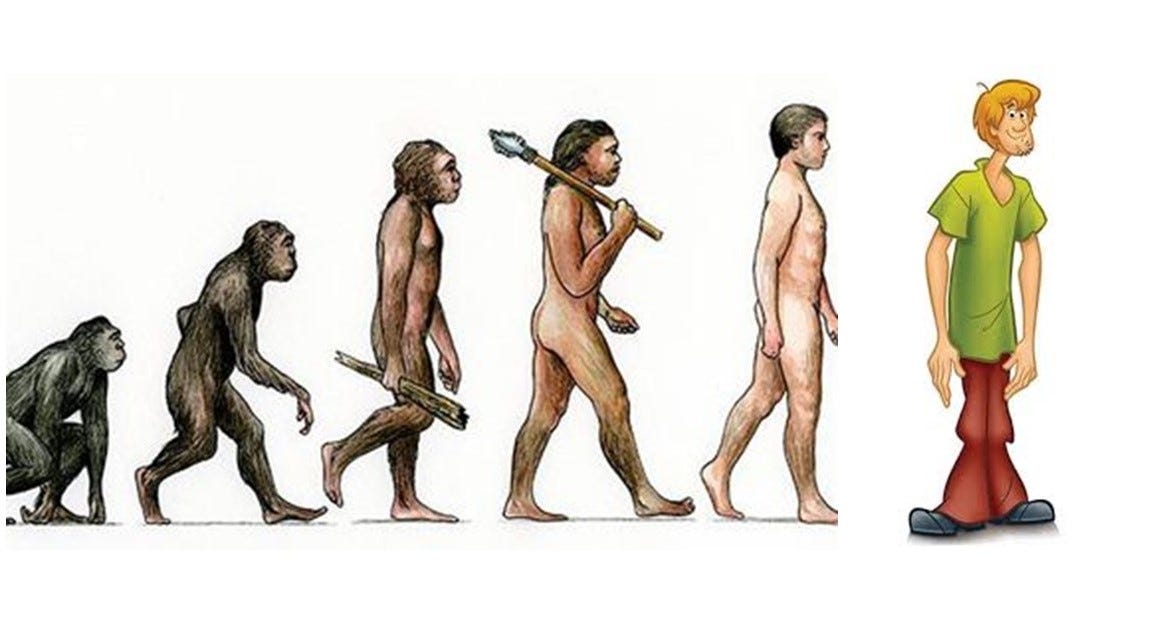

超人と亜人

The dark side of this spiritual Darwinism is a tendency to classify other humans, other groups, other races, as backward, degenerate, animalistic, unfit, and requiring control, confinement, sterilization and possibly extinction.

この精神的ダーウィニズムの暗黒面は、他の人間、他のグループ、他の人種を、後進的、退化的、動物的、不適格なものとして分類し、管理、監禁、不妊化、そして場合によっては絶滅を必要とする傾向にあります。

To take one example, we could consider Richard M. Bucke’s book Cosmic Consciousness (1901). It’s a very influential text, arguably foundational for the New Age, for transpersonal psychology, and for psychedelic culture. It’s also an exceedingly strange book.

一例を挙げるならば、リチャード・M・バック ※1 の著書『宇宙意識』(1901年) ※2 があります。この本は、ニューエイジ、トランスパーソナル心理学、サイケデリック・カルチャーの基礎となったと言っても過言ではないほど、影響力のあるテキストです。この本は、非常に奇妙な本でもあります。

Bucke argues that a handful of humans — mainly him and his friends — have attained an experience called ‘cosmic consciousness’, which are the first rays of the dawning of a new species. This new species will appear more and more, and eventually run the world and supersede homo sapiens.

バックは、一握りの人間(主に彼とその友人)が「宇宙意識」と呼ばれる体験を得ており、それが「新種の夜明けの最初の光である」と主張している。「この新種はどんどん現れて、やがて世界を牛耳り、ホモ・サピエンスに取って代わるだろう」と。

While preaching this coming evolutionary shift, Bucke was also a psychiatrist running an asylum in Ontario. He believed insanity was caused by defective sexual organs, and operated on hundreds of women under his care. He also believed some races were incapable of cosmic consciousness and were fated to become extinct.

バックは、このような「進化の時代の到来」を説く一方で、オンタリオ州で精神科医として精神病院を運営していました。彼は狂気の原因が性器の欠陥にあると考え、何百人もの女性を手術しました。また、「ある種の人種は宇宙意識を持つことができず、絶滅する運命にある」と考えていました。

In many pioneers of the ‘human potential movement’ one finds a similar attitude. ‘People like us’ are the evolutionary elite, the peak experiences, the transcenders, the first buds of homo novus. But we are surrounded by morons, mental defectives languishing at the bottom of the evolutionary scale. These subhumans or untermenschen should be controlled, confined and possibly sterilized, so that elite humanity can evolve to its full potential.

「ヒューマン・ポテンシャル・ムーブメント(人間性回復運動)」 ※3 の先駆者たちの多くには、同じような態度が見られます。「私たちのような人間」は、進化のエリートであり、ピーク体験者であり、超越者であり、ホモ・ノバスの最初の芽である。しかし、私たちの周りには、進化のスケールの底辺に位置する白痴や精神的欠陥者がいる。これらの亜人やウンターメンシェン ※4 は制御され、監禁され、場合によっては不妊化されるべきであり、そうすればエリート人類はその可能性を最大限に進化させることができる。

One finds this Nietzschean categorization of humanity into superhumans and subhumans in the ideas of HG Wells, Madame Blavatsky, Annie Besant, Aldous and Julian Huxley, Alexis Carrel, Sri Aurobindo, and many others from the New Age / progressive / psychical research occulture of the 1890s-1930s. And it appears again in the human potential movement of California after the war.

H・G・ウェルズ ※5 、マダム・ブラヴァツキー ※6 、アニー・ベサント ※7 、オルダス・ハクスリー ※8 とジュリアン・ハクスリー ※9 のハクスリー兄弟、アレクシス・カレル ※10 、スリ・オーロビンド ※11 など、1890年代から1930年代にかけての「ニューエイジ / プログレッシブ / サイキック・リサーチ・オカルチュア」に属する多くの人々の思想の中に、この「ニーチェ的な人類の超人と亜人への分類」が見られる。そしてそれは、戦後のカリフォルニアの「ヒューマン・ポテンシャル・ムーブメント」の中に再び現れた。

※ ニーチェの信奉者であるマズローは、ピラミッドの頂点に立って「自己超越者」になれるのは一握りの人間だと考えていました。

サイケデリックと進化論的スピリチュアリティ

Now it’s interesting to consider this overlap of the human potential movement and Nietzschean eugenics with regard to psychedelics.

さて、サイケデリックに関して、「ヒューマン・ポテンシャル・ムーブメント」と「ニーチェ的優生学」が重なっていることを考えるのは興味深いことです。

So far, I don’t think there has been much work done on the relationship between the histories of psychedelics and eugenics, but it’s there. To take two examples, Havelock Ellis and Aldous Huxley, two of the first westerners to take and write about mescaline, were both lifelong champions of eugenics.

これまでのところ、「サイケデリックの歴史と優生学との関係」についてはあまり研究されていないと思いますが、それは実際に存在しています。2つの例を挙げると、メスカリン ※12 を飲んで書いた最初の西洋人であるハヴロック・エリス ※13 とオルダス・ハクスリー ※8 は、どちらも生涯にわたって優生学の擁護者でした。

The post-war culture of psychedelics was shaped by the spiritual Darwinism / evolutionary spirituality of Modernist elitists like Huxley and his friend Gerald Heard.

戦後のサイケデリック文化は、ハクスリーやその友人ジェラルド・ハード ※14 のようなモダニストのエリートたちの「精神的ダーウィニズム / 進化論的スピリチュアリティ」によって形成されました。

Psychedelics are seen as the catalyst for the evolutionary advancement of….who? The select few? The young? The beautiful people? Everyone?

For Timothy Leary, LSD was ‘creating a new race of mutants’. This new master-race would, eventually, run the world. For Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters, LSD was likewise creating a new race of superheroes, telepathically connected and able to control global events. Terence McKenna and Daniel Pinchbeck also describe psychedelics as evolutionary catalysts for the dawning of a new era, a new level of consciousness, a whole new species.

ティモシー・リアリー ※15 にとって、LSD ※16 は「ミュータントの新しい人種を作り出すもの」でした。この新しい種族が、最終的には世界を支配することになるだろう。ケン・キージー ※17 とメリー・プランクスターズ ※18 にとって、LSDは同様に、「テレパシーでつながり、世界の出来事をコントロールできるスーパーヒーローの新しい種族」を生み出していました。テレンス・マッケナ ※19 とダニエル・ピンチベック ※20 もまた、「サイケデリックは新しい時代、新しいレベルの意識、全く新しい種の幕開けのための進化の触媒である」と述べています。

McKenna’s famous book, Food of the Gods (1992), shares its title from HG Wells’ eugenic sci-fi tale of 1904, in which some humans consume a magic chemical which makes them grow far superior to ordinary humanity. The ‘Children of the Food’ are destined to surpass homo sapiens. A similar story is told in Arthur C. Clarke’s Childhood’s End (1953), a favourite text of the Merry Pranksters.

マッケナの名著『神々の糧(Food of the Gods)』(1992年) ※21 のタイトルは、H・G・ウェルズ ※5 が1904年に発表した優生学的なSF物語と同じである。「食物の子供たち」はホモ・サピエンスを凌駕する運命にある。同様の話は、アーサー・C・クラーク ※22 の『幼年期の終わり』(1953年) ※23 にも描かれており、メリー・プランクスターズのお気に入りのテキストでもある。

It’s not clear, then, if everyone will make the evolutionary leap, or just a few cosmic mutants. This was — and remains — a lively debate in psychedelic circles. Are psychedelics for everyone? Can everyone handle them?

「すべての人が進化を遂げるのか?それとも一部の宇宙的なミュータントだけが進化を遂げるのか?」それは、はっきりしていません。これはサイケデリック界隈での活発な議論であり、今でもそうです。サイケデリックは万人向けなのか?誰もがサイケデリックを扱えるのか?

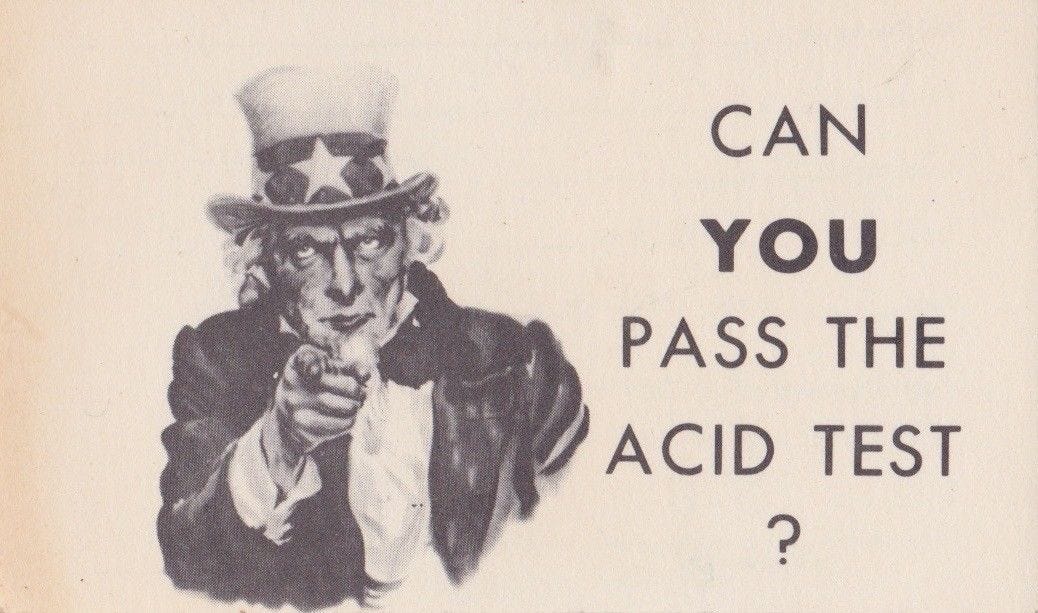

Within the context of this spiritual Darwinism, it’s interesting to think of psychedelics as ‘the acid test’ — the test of one’s fitness to join the next stage, the evolutionary elite of superheroes.

このスピリチュアル・ダーウィニズムの文脈において、サイケデリックを「アシッド・テスト」、つまり「進化的エリートである超人となる人間の次のステージに参加するための適性テスト」と考えるのは興味深いことです。

There have been previous versions of ‘the test’. For Thomas Malthus, it was ‘are you economically productive?’ For Darwin it was ‘have you reproduced?’ For Francis Galton and other meritocrats, it is ‘can you pass the exam?’ For Ernst Junger, it was ‘can you fight with courage?’

この「テスト」には「過去バージョン」がありました。トーマス・マルサス ※24 にとっては、「あなたは経済的に生産的ですか?」ダーウィンにとっては「あなたは繁殖しましたか?」フランシス・ゴルトン ※25 やその他の実力主義者にとっては「試験に合格できるか?」エルンスト・ユンガー ※26 にとっては、「勇気を持って戦えるか?」

For psychedelic Darwinians, it is ‘can you handle a heroic dose?’

サイケデリックな進化論信望者たちにとって、それは「英雄的な投与量を扱えるかどうか?」である。

Within this frame, it’s obviously pretty brutal if you have a bad trip and freak out. You have failed the acid test. You are not a superhuman after all. In fact, in some ways you’re less than human. You’re on the rubbish dump of evolution.

この枠組みの中で、バッドトリップしてパニックになったら、明らかにかなり残酷ですよね?それは「あなたはアシッドテストに失敗したのだ」ということを表します。あなたは所詮、超人ではない。それどころか、ある意味では人間以下の存在だ。あなたは「進化のゴミ捨て場にいる」のです。

As a side note, it’s interesting to consider how all these psychedelic leaders somehow ‘failed the test’ — Leary runs from the Buddha in Varanasi, Ken Kesey blows the ‘acid graduation’, Terence McKenna fails to build his alien artefact, Daniel Pinchbeck fails to incarnate as Quetzalcoatl in 2012 and instead pervs on women. These could all be interpreted as variations of Joseph Conrad’s Lord Jim, the ultimate story of ‘failing the test’.

リアリー ※15 はバラナシの仏陀から逃げ出し、ケン・キージー ※17 は「アシッドの卒業式」を吹き飛ばし、テレンス・マッケナ ※19 はエイリアンのアーティファクト(人工物・工芸品)を作ることに失敗し、ダニエル・ピンチベック ※20 は2012年にケツァルコアトル(アステカ神話の文化神・農耕神)として受肉することに失敗し、代わりに女性に色目を使っています。これらはすべて、ジョゼフ・コンラッド ※27 の『ロード・ジム』 ※28 のバリエーションとして解釈することができ、「テストに失敗する」ことの究極の物語である。

Personally speaking, I totally bought into the mythology of the Merry Pranksters when I was a teenage raver. I also thought of myself as ‘young, immune’…a superhero! So when I had a bad LSD trip aged 18, and felt shattered for months afterwards, I took it as a colossal failure, a proof of my unfitness, even my unworthiness to exist.

個人的には、私は10代のレイバーだった頃、メリー・プランクスターズ ※18 の神話を完全に信じていました。自分のことを「若くて免疫がある」と思っていたし、スーパーヒーローだとも思っていた。だから、18歳のときにLSD ※16 トリップでひどい目に遭い、その後何ヶ月も打ちのめされたときは、大失敗であり、自分が不適格であること、さらには存在価値がないことを証明していると受け止めました。

So one can see how these sorts of rigid either / or classifications of ecstatic experience can play out in harsh and dehumanizing ways.

このように、「恍惚とした経験を厳格にどちらかに分類すること」が、いかに過酷で非人間的な方法で行われるかがわかります。

すべての精神病体験は、潜在的に「スピリチュアル・エマージェンシー」なのでしょうか?

Let’s return, finally, to the Grofs’ concept of ‘spiritual emergency’.

最後に、グロースの「スピリチュアル・エマージェンシー」という概念に話を戻そう。

In some ways, the concept was a very helpful advance from the unfortunately rigid classification of ecstasy as either pathological and totally bad, or divinely inspired and totally good.

ある意味では、この概念は、「エクスタシーを病的で完全に悪いものと、神の霊感で完全に良いもののどちらかに分類する」という、残念ながら厳格な分類からの非常に有益な前進でした。

It recognized a middle-ground, admitting that ecstatic experiences can be both beautiful and terrifying, both meaningful and bewildering, both empowering and traumatizing, both connecting and alienating.

それは、「恍惚とした体験は、美しくもあり恐ろしくもあり、意味深くもあり当惑させるものでもあり、力強くもありトラウマにもなるものでもあり、全てとの繋ながり感覚もあれば疎外感もある」ことを認め、「中間的な立場を認めたもの」です。

However, as Noorani points out, there is still the sort of defensive manoeuvre we saw at earlier stages in the history of transpersonal psychology.

しかし、ヌーラニ(Tehseen Noorani)が指摘するように、トランスパーソナル心理学の歴史の初期段階で見られたような防衛策がまだ存在しています。

The Grofs insist, to paraphrase, these experiences — spiritual emergencies — are part of elite humanity’s evolutionary transition to a higher level of consciousness.

グロウズは、言い換えれば、これらの経験(スピリチュアル・エマージェンシー)は、エリート人類が高次の意識レベルへと進化するための一部であると主張している。

Those experiences — common-garden psychotic experiences — are merely mental illness, probably organic or physiological in nature, and indicative of evolutionary regression.

このような経験、つまり一般的な精神病の経験は、単なる精神疾患であり、おそらく本質的には器質的または生理的なものであり、進化的退行を示しているのです。

These experiences happen to people like us, people engaged in advanced spiritual practice, Esalen people, self-transcenders. Rich, educated, white people. The elite.

このような体験は、私たちのような、高度な精神修養に従事する人々、エサレン(アメリカのヒッピーの聖地) ※29 の人々、自己超越者たちに起こります。金持ちで、教育を受けた、白人。エリートですね。

Those experiences happen to other people, at the bottom of the pyramid, ‘mass man’.

それらの体験は、ピラミッドの一番下にいる「大衆」という他の人に起こるものです。

What my co-editor Tim Read and I found, when we gathered together accounts of ‘spiritual emergencies’ for the book Breaking Open: Finding a Way through Spiritual Emergency, was that it was not in practice very easy to draw a clean line between spiritual emergency and psychosis.

共同編集者であるティム・リードと私は、『Breaking Open: Finding a Way through Spiritual Emergency』という本のために「スピリチュアル・エマージェンシー」の証言を集めたとき、分かったことがあります。実際には、「スピリチュアルな緊急事態と精神病との間に明確な線を引くことはあまり容易ではない」ということが。

Some of our contributors had temporary psychotic experiences after taking psychedelics or after intense spiritual practice. Some crises were triggered by a bereavement, personal crisis, or even a political crisis.

また、サイケデリックを服用した後や、激しい精神修養を行った後に、一時的に精神病を経験した人もいました。また、死別や個人的な危機、さらには政治的な危機がきっかけとなった危機もありました。

Sometimes it was a one-off experience, sometimes it happened more often.

「一度だけの経験」の場合もあれば、「頻繁に起こる」場合もありました。

Sometimes it was subsequently interpreted entirely positively by the experiencer, sometimes it was interpreted more ambiguously.

その後、体験者が「完全に肯定的に解釈すること」もあれば、「曖昧に解釈すること」もありました。

What these experiences had in common, what makes the label ‘spiritual emergency’ somewhat useful, is that the people who had the experience felt there was something meaningful in it. They felt the experience was both awe-inspiring and also terrifying. The experiences felt ecstatic, even mystical. They didn’t feel simply delusional and pathological.

これらの体験に共通しているのは、「スピリチュアル・エマージェンシー」という言葉が役に立つのは、「体験者がその体験に何か意味があると感じているから」です。「畏敬の念を抱くと同時に、恐怖を感じていた」のです。と同時に、「恍惚とした、神秘的な体験」でもありました。単なる妄想や病的なものではありませんでした。

Almost all our contributors also found certain self-care and mutual aid practices helpful, such as finding a calm, supportive and safe environment; grounding themselves in the body and in material reality; finding sympathetic people to connect to; and seeing their experience through a frame of kindness, patience and potential growth, rather than a frame of breakdown and disease.

また、ほぼすべての回答者が、「セルフケアや相互扶助の実践に役立った」と考えています。例えば、「穏やかで協力的な安全な環境を見つけること」、「身体や物質的な現実に身を置くこと」、「共感してくれる人を見つけること」、「故障や病気の枠ではなく、優しさや忍耐、潜在的な成長の枠で自分の経験を見ること」などが挙げられます。

For all of our contributors, their crises did not mark the start of a long slide into worse mental functioning.

危機に陥っても、精神機能の低下を招くことはありませんでした。

What caused these crises? We simply don’t know. We don’t know to what extent the causes were genetic, physiological, chemical, cognitive, social, economic or spiritual. But it’s likely to be a combination of all these levels. It doesn’t have to be either physiological or developmental or cognitive-spiritual.

これらの危機の原因は何か?私たちは単純にまだ知りません。「遺伝的、生理的、化学的、認知的、社会的、経済的、精神的にどの程度の原因があるのか?」はわかりません。しかし、「これらすべてのレベルの組み合わせである可能性は高い」と思います。「生理的なもの、発達的なもの、認知的・精神的なもののいずれか」である必要はありません。

Nor do treatments have to be either cognitive-spiritual or chemical. Some of our contributors find medication helpful, others don’t.

また、「治療法は、認知的精神的なものや化学的なもののいずれか」である必要はありません。薬物療法が有効な人もいれば、そうでない人もいます。

As Mike Jackson ※30 and Charles Heriot-Maitland ※31 have noted, it’s difficult to draw a clean line between mysticism and psychosis — experiences of ego dissolution exist on a continuum, depending on how much insight and skilful means a person has to navigate the experience, and also depending on how supportive their cultural and socio-economic context is.

Mike JacksonやCharles Heriot-Maitlandが指摘しているように、神秘主義と精神病の間に明確な線を引くことは困難です。「自我の解消の経験」は、その人がどれだけの洞察力と巧みな手段を持っているか、また文化的、社会経済的な背景がどれだけ支えになっているかによって、連続的に存在します。

In conclusion, the term ‘spiritual emergency’ was helpful in marking out a middle-ground between ‘psychosis’ and ‘spiritual experience’. But transpersonal psychologists tried too hard to bracket off this type of experience from common-garden psychosis rather than admitting a continuum. As a result, the term itself has not had much influence, even within New Age and psychedelic circles.

結論として、「スピリチュアル・エマージェンシー」という言葉は、「精神病」と「スピリチュアルな体験」の間の中間領域を示すのに役立ちます。しかし、トランスパーソナル心理学者は、この種の体験を一般的な精神病から切り離そうとするあまり、連続性を認めようとしませんでした。その結果、ニューエイジやサイケデリックの世界でも、この言葉自体があまり影響力を持たなくなってしまいました。

Can we not extend the same respect and dignity to psychosis in general as we do to spiritual emergencies?

一般的な精神病に対しても、「スピリチュアル・エマージェンシー」に対するのと同じような敬意と尊厳を払えないものでしょうか?

In other words, can we recognize that for some people, psychotic experiences are not simply breakdowns or symptoms of disease, but also sometimes beautiful, meaningful, and even spiritual experiences?

つまり、人によっては、精神病体験が単なる故障や病気の症状ではなく、時には美しく、意味のある、スピリチュアルな体験であることを認めることができるのではないでしょうか?

Can we recognize that labels are sometimes helpful, but they are also crude and historically contingent classifications of mental states that are dynamic and hard to pin down?

「ラベル付け(レッテル貼り)」は役に立つこともありますが、それは「動的で特定するのが難しい精神状態の、粗雑で歴史的に偶発的な分類でもあること」を認識できるでしょうか?

Mental experiences in general, and ecstatic experiences in particular, are ambiguous. They are not well-approached with rigid either / or classifications. They are not easy to pin on a map, to say ‘this was nothing but a brain pathology’ or ‘this was definitely a shamanic initiation’ or ‘this was definitely the cave descent on the hero’s journey’ or ‘this was definitely a spiritual emergency on the path to an evolutionary shift’.

一般的な精神的な経験や、特に恍惚とした経験は、曖昧なものです。厳密にどちらか、あるいはどちらかに分類することはできません。「これは脳の病理に過ぎない」とか、「これは間違いなくシャーマニックなイニシエーションだ」とか、「これは間違いなく英雄の旅の洞窟下りだ」とか、「これは間違いなく進化の道を歩む上での精神的な緊急事態だ」などと、地図上で特定することは容易ではありません。

Our maps are crude, not to be confused with the territory itself. Instead of fixating on labels or causes, we can shift our focus to ‘what helps now?’

私たちの地図は粗いものですが、その領域自体と混同してはいけません。ラベルや原因に固執するのではなく、「今、何が役に立つのか?」に焦点を移すことができます。

Mental states and indeed all experiences are not essentially ‘good’ or bad’. It depends on the view you take of them. That’s as true of cancer as it is of psychosis.

精神状態やあらゆる経験は、本質的に「良い」ものでも「悪い」ものでもありません。それは、「あなたがそれらをどのように捉えるか?」によります。これは、精神病と同様に癌にも言えることです。

As Noorani has suggested, we need to consider our classification of psychosis as the terrifying Other of our rational civilization.

ヌーラニ(Tehseen Noorani)が提案したように、私たちは「精神病」という分類を、私たちの「合理的な文明の恐るべき他者」として考える必要があります。

Altered states of consciousness are something that happens to lots of people. They’re neither totally bad nor totally good. Neither proof of our unfitness, nor proof of our divine election.

「意識の変化」は、多くの人に起こることです。それらは完全に悪いものでもなければ、完全に良いものでもない。私たちが不適任であることの証明でもなければ、神に選ばれたことの証明でもありません。

It depends on how we relate to them.

それは、「私たちがどのように関わるか?」によります。

I hope we can learn to support people to come to terms with their experiences, to make friends with them, and to find ways to integrate them, including self-care, mutual aid, economic support, and if it’s helpful medication.

私たちは、人々が自分の経験に折り合いをつけ、その経験と友達になり、セルフケア、相互扶助、経済的支援、そして役に立つ場合には投薬など、それらを統合する方法を見つけるためのサポートを学べることを願っています。

‘Coming to terms’ means finding the frame, the view, and the terminology that you find liberating. ‘Spiritual emergency’ is one such term, not perfect, but sometimes useful.

「折り合いをつける」とは、自分が解放されるようなフレーム、見解、用語を見つけることです。「スピリチュアル・エマージェンシー」はそのような用語の一つであり、完璧ではありませんが、時には役に立ちます。

(翻訳ここまで)

medium.com より翻訳引用

※1

リチャード・モーリス・バック(Richard Maurice Bucke, 1837年3月18日 - 1902年2月19日)は、モーリス・バックと呼ばれ、19世紀後半のカナダの著名な精神科医である。

青年期に冒険家だったバックは、後に医学を学んだ。後に精神科医となり、オンタリオ州ロンドンの州立精神病院の責任者となった。バックは、カナダ、アメリカ、イギリスの著名な文学者たちと親交があった。

専門的な論文を発表する一方で、3冊のノンフィクションを執筆。人間の道徳的本質』、『ウォルト・ホイットマン』、『宇宙意識』。代表作は『人間の道徳性』、『ウォルト・ホイットマン』、『宇宙意識:人間の心の進化についての研究』。

※2

※3

※4

※5

※6

※7

※8

※9

※10

※11

※12

※13

※14

ヘンリー・フィッツジェラルド・ハード(1889年10月6日~1971年8月14日)は、イギリス生まれのアメリカ人歴史家、科学作家、講演家、教育者、哲学者である。多くの記事と35冊以上の本を執筆した。

1950年代から1960年代にかけて、ヘンリー・ルースやクレア・ブース・ルース、アルコール依存症の共同創始者であるビル・ウィルソンなど、数多くの著名なアメリカ人を指導した。また、1960年代以降に欧米で広まった意識開発運動の先駆者であり、影響を与えた人物でもある。

※15

※16

※17

※18

※19

※20

※21

※22

※23

※24

※25

※26

※27

※28

※29

※30

※31

著者紹介

ジュールス・エバンス

「Philosophy for Life」などの著書がある。

「Centre for the History of the Emotions(感情史センター)」名誉研究員。

http://www.philosophyforlife.org/

↓良ければポチっと応援お願いします↓